-

Resource

Do Rh negative women who experience first trimester loss or who obtain a first trimester abortion require immunization with rho (d) immunoglobin (RhoGAM)?

Rh negative women who become exposed to Rh positive blood may become ‘alloimmunized,’ or develop anti-Rh antibodies. Women with Rh alloimmunization may have complications in … <a hr…July 29, 2015

-

Resource

Counseling for Miscarriage Management

Miscarriage is often an emotionally charged event in a woman’s life. A woman diagnosed with early pregnancy loss or incomplete miscarriage has several treatment options, … <a href="https://ww…May 19, 2015

-

Resource

Teaching Pain Management for Uterine Aspiration

In caring for patients undergoing a uterine aspiration procedure, there are a number of techniques a clinicians can practice to reduce patient pain and discomfort. … <a href="https://www.innova…February 11, 2015

-

Resource

A Practical Guide for Establishing a Jail Rotation

Carolyn Sufrin, MD, PhD A rotation where Ob/Gyn residents care for women in prison and jail can be a transformative experience for residents and provides … <a href="https://www.innovating-educa…October 2, 2014

-

Resource

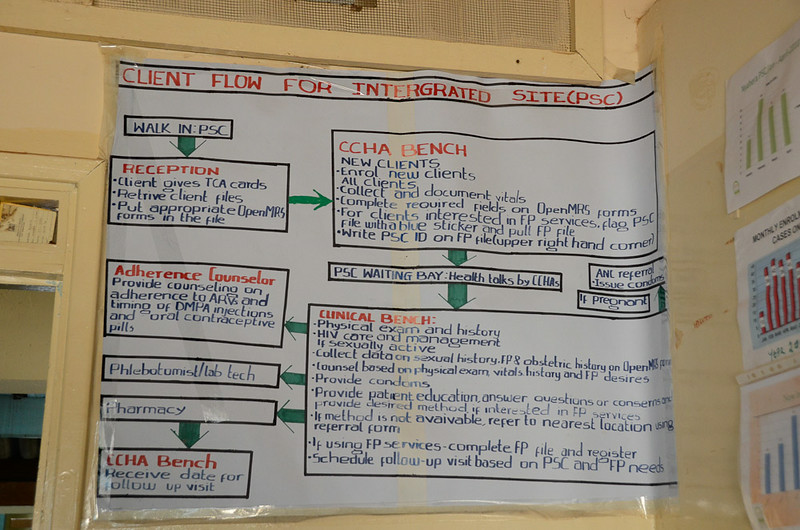

The Importance of Family Planning Training in Zimbabwe: Part Two

During the last week I was in Zimbabwe, I had the opportunity to spend some time at Harare hospital. Harare hospital established a post-abortion care … <a href="https://www.innovating-education…September 2, 2014

-

Resource

The Importance of Family Planning Training in Zimbabwe: Part One

Recently, I had the opportunity engage in some family planning clinical work in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe is in southern Africa, and is a country that has … <a href="https://www.innovating-education.o…August 5, 2014

-

Resource

Where are the Nurses in Abortion Care?

There are no clear guidelines for managing conscientious objection in nursing; not only is it tolerated, but in many institutions, it becomes an unwritten policy. … <a href="https://www.innov…July 15, 2014

-

Resource

Notes From a Full Spectrum NurseMidwifery Student, Part II

Guest Post: Holly Carpenter, RN, CNM Candidate, UCSF Both APC and pre-licensure nursing students still face a fairly bleak picture in terms of standard SRH … <a href="https://www.innovating-edu…December 6, 2013

-

Resource

Notes From a Full Spectrum NurseMidwifery Student, Part I

Guest Post: Holly Carpenter, RN, CNM Candidate, UCSF When I was choosing between various CNM (certified nurse midwifery) Master’s programs in 2010, the faculty biographies … <a href="https://…October 2, 2013

Sort

Filter by Type

Filter by Topic